Up in the mountains of Kaala, a group of Westside students sat in a hale to reflect on their experience as Westside kids.

“What do people say about us out here in Waianae?” asks Kristyn Kailewa, a 2020 Waianae High School graduate.

Her peers shout, “ghetto,” “lazy” and “dumb,” among other criticism that they are used to hearing about their home. The group agreed that a lot of what they thought about themselves was told or taught to them.

Through tears, the group of 16 Waianae and Nanakuli students wrestled with their identity as Westside kids.

“But we’re better than that!” says Kornelious Tabag, a senior at Nanakuli Intermediate and High School. “Through these five weeks, we got to show the true values that we have.”

In an effort to more deeply engage and provide resources for the communities we cover, we created a community bulletin board. Send us your event flyers, volunteer opportunities, notices of school and neighborhood board meetings and other happenings in your community.

Post To Our Community Bulletin Board

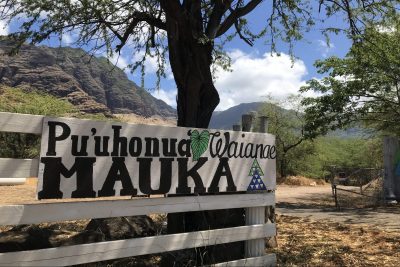

The students participated in Pua Kaiaulu, a place-based internship for Waianae and Nanakuli high schoolers. Students learned the history of the Waianae Coast through hands-on work. The driving question for the program asked students how their personal stories contribute to the story of Waianae.

Over the course of five weeks, students in the program strengthened their understanding of place but also their own identities as Westside residents and their role in the community.

‘The Story Of Our Place’

Pua Kaiaulu is the first summer program put on by PLACES, a grant-funded project from University of Hawai’i at Mānoa’s Office of Student Equity, Excellence & Diversity. As an acronym for Place-based Learning And Community Engagement in School, the project started with after-school programs for students at Waianae High School, Nanakuli Intermediate and High School and Ka Waihona o Ka Naʻauao Public Charter School.

Harvesting salt from local waters. Starting small gardens. Running mini farmer’s markets. The program offers all of these after-school activities and more for students to get out of the classroom and into the community.

“Kids need to know about where they live and the strengths of their community,” Kay Fukuda says.

As the program director of PLACES, she and her team of six coordinators put on various programs throughout the year on the Waianae Coast. And she says the location was a deliberate decision.

“We are amazed at the intellectual, cultural and spiritual depth that exists there,” Fukuda explains. ”So we are trying to figure out how to make all their knowledge accessible to students.”

Fukuda, a graduate of Waipahu High School, says that when she was growing up, Waianae just wasn’t a place you went to in the 1970s, but she believes that that perception can change.

“In everything we do, we’re always creating our story of who we are and who our community is,” Fukuda says.

‘How We Always Learned’

Haumana –– or students — got to choose between different focuses as they went through the Pua Kaiaulu program. Whether it was fire mitigation, water access, ancestral practices or land use and policy, the groups represented the different responsibilities in taking care of an entire ahupuaa, or land division.

“As Hawaiians, this is how we always learned things,” Camille Hampton says.

Hampton, an instructional coach at Waianae High School, worked behind the scenes in coordinating and setting up the curriculum for the high schoolers. From mauka to makai, the juniors and seniors learned everything from weaving coconut hats to the historical water diversion from Waianae to the proper removal of invasive plants. Every Monday, they would learn moolelo — or stories — of the different areas, from stories of the Hawaiian demigod Maui to a commoner named Manawahua.

Most of their huakai — or field trips — took them to different parts of Waianae. Meeting local leaders, like Department of Hawaiian Homelands Chairman William Aila Jr. and Ka‘ala Farm founder Eric Enos, allowed them to see firsthand the issues their community faces and the people working to address them.

“This was one of our most successful internships because we were all learning together,” Enos says.

As a partner on the Pua Kaiaulu program, he told his own story about bringing water to Ka‘ala Farm in the 1970s and the importance of water flow through an ahupua‘a. Talking to Enos inspired many of the kids to learn more about the Waianae watershed.

“We have to connect them with our leaders now if we want them to be the leaders of the next generation,” Shannon Bucasas says.

Bucasas, a Waianae High School teacher and the leader of the fire mitigation hui at Pua Kaiaulu, says the community is the best teacher for the students, especially if they want to stay connected to their home. She believes that having love and understanding of their place can ignite a personal passion to serve.

Teachers like Hampton and Bucasas emphasize that this style of learning – with freedom and flexibility – should be incorporated into the school curriculum. Their motto throughout was the ‘olelo no‘eau “Ma Ka Hana Ka Ike,” meaning “to learn by doing.”

But the fight for more place-based learning experiences comes with its challenges.

Hampton feels it’s been an “uphill battle” in justifying the need for place-based learning to her administration. She says it’s hard for teachers to afford the time and resources to put out-of-classroom activities into a traditional, linear curriculum.

How do students apply hard skills, like math and science, into an outdoor activity? How valuable are soft skills, like teamwork and reflection? How do you know if kids are really learning?

Hampton says that strengthening a sense of belonging and responsibility in students motivates them to do the kind of work that students may not want to do, like writing papers and taking tests.

“It’s like pulling teeth to get kids to do academic work, but when they’re connected to the topic, they are more willing to do it,” Hampton says.

‘This Is Aina Work’

Ayla Vega describes herself as a “pretty decent” student with mostly As and Bs on her report card. Although she admits she didn’t do as well distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, she was ready to ditch the screens and be amongst her peers in the Pua Kaiaulu program.

“Coming out here makes me feel free because I am actually putting what I learned into the world,” Vega says.

The Waianae High School senior has always had a strong sense of place. She says there is a different kind of mana – or power – in Waianae and this program has taught her how to channel that pride into community action.

Vega joined Bucasas’ fire mitigation group because of her interest in native plants. Not really the outdoorsy type, her perspective changed when she was up in the Ka‘ala mountains, learning seed propagation and weed management. Waianae experiences an average of 35 fires per year, much more than any other island and higher than the national average. She knew it was important to learn why the fires happen and how to prevent them.

“If we know we have a lot of wildfires, what is the community doing about it and how can we help?” Vega asks.

She’s looking forward to her last year of high school and is newly motivated to share the ike – or knowledge – that she learned. More than just place-based learning, she believes that it is all “aina work” and hopes that other students can have opportunities to work outside and feel the deepened sense of place she knows now.

“Your place is where your heart is,” Vega says. “It’s the land and the people who keep you grounded.”

Hear from these students about their experience:

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

Sign up for our FREE morning newsletter and face each day more informed.

About the Author

-

Ku'u Kauanoe is the engagement editor for Honolulu Civil Beat. You can reach her by email at kkauanoe@civilbeat.org

Ku'u Kauanoe is the engagement editor for Honolulu Civil Beat. You can reach her by email at kkauanoe@civilbeat.org

Support Independent, Unbiased News

Civil Beat is a nonprofit, reader-supported newsroom based in Hawaiʻi. When you give, your donation is combined with gifts from thousands of your fellow readers, and together you help power the strongest team of investigative journalists in the state.

Every little bit helps. Will you join us?

More Stories In This Special Report

-

Part 1

Part 1There Are 10 Community Gardens On Oahu. None Of Them Are On The Westside

-

Part 2

Part 2West Oahu Residents Say The Media Is Getting Their Community All Wrong. We Want To Change That

-

Part 3

Part 3A Community Garden Is A Must-Have For West Oahu

-

Part 4

Part 4Veterans Near End Of Fight To Return Barbers Point Memorial To West Oahu

-

Part 5

Part 5These Makaha Residents Are Hoping To Move A Major Highway

-

Part 6

Part 6How The Westside Is Restoring The Coconut Tree As A Food Source In Hawaii

-

Part 7

Part 7Union Says Ongoing Closure Of Health Clinic In Nanakuli Is ‘Equity Issue’

-

Part 8

Part 8Battle Of Midway Commemorated As Rebuilt Barbers Point Memorial Unveiled

-

Part 9

Part 9Activists Hit New Roadblock In Efforts To Reroute Farrington Highway At Makaha Beach

-

Part 10

Part 10HDOT Changes Plans For Farrington Highway Bypass After Community Protests

-

Part 11

Part 11These West Oahu Residents Are On A Mission To Clean Up The Island’s Beach Parks

-

Part 12

Part 12How One Hawaii Man Is Using An Invasive Tree To Nurture His Community

-

Part 13

Part 13Here’s How A ‘Perfect Storm’ Led To A Spike In COVID Cases On The Westside

-

Part 14

Part 14Westside Students Learn About Waianae Coast — And Themselves

-

Part 15

Part 15A Shaky Truce: The Army And Native Hawaiians Both Want Oahu’s Makua Valley

-

Part 16

Part 16How Do You Build A Community From Scratch? This Homeless Advocate Is Trying

-

Part 17

Part 17Can The Rich History Of Ewa Villages Spark A New Sense Of Community?

-

Part 18

Part 18West Oahu Residents Are Wary Of Possible Marine Corps Expansion

-

Part 19

Part 19The Next Community To Host Oahu’s Landfill Can Learn From The Westside

-

Part 20

Part 20Are Tiny Homes The Answer To Homelessness? Hawaii Is Giving Them A Try

-

Part 21

Part 21From ‘Sacred Place’ To ‘Dumping Ground,’ West Oahu Confronts A Legacy Of Landfills

-

Part 22

Part 22West Oahu Reps Plan To Tackle Traffic, Tech And The Cost Of Living