By T.R. Witcher

“The German invasion and occupation of Norway and Denmark in April 1940 set off alarm bells in Washington,” wrote Alfred Goldberg, chief historian for the Office of the Secretary of Defense, in his 1992 book on the history of the Pentagon (The Pentagon: The First Fifty Years, Historical Office, Office of the Secretary of Defense). “But it was the smashing German blitzkrieg victories over the French and British in May and June and the fall of France that shocked the U.S. government into taking immediate action to rearm the nation against potential and increasingly potent enemies.”

According to Goldberg, by summer 1941 the Army had grown from a force of about 270,000 only a year before to more than 1.4 million men, including 630,000 draftees and more than a quarter million National Guard members — and it was adding more troops daily. Army leaders were frantically trying to build camps and other facilities around the country to house, equip, and train this growing fighting force. But back in Washington, D.C., an equally pressing question loomed: Where would America’s military leadership be headquartered?

The answer — the Pentagon — may seem almost inevitable in hindsight, but on the eve of World War II, the building’s shape, location, size, and really its very existence was hardly a foregone conclusion. Given the structure’s storied past, especially now, on the eve of the 20th anniversary of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, the Pentagon has emerged as the one building that, as much as any, symbolizes the power, progress, and trials of the United States over the last three quarters of a century.

In the early 1940s, as WWII was engulfing ever more nations, the U.S. War Department was about to open a new $18 million (nearly $300 million in today’s dollars) headquarters — a “big, neoclassical structure” in the city’s Foggy Bottom neighborhood, just north of the Lincoln Memorial, according to military reporter Steve Vogel in his 2008 history of the building, The Pentagon (New York City: Random House Trade Paperbacks). It was designed to hold about 4,000 people. At that point, there were roughly 24,000 War Department staff scattered across 23 buildings. The new building would reduce the need to 17 buildings — but more staffers were coming. The number, Vogel wrote, was expected to reach 30,000 by year’s end. The War Department would need another 734,000 sq ft of office space and 300,000 sq ft for records storage.

By spring 1941, Secretary of War Henry Stimson told President Franklin D. Roosevelt the news: Despite the new headquarters, the War Department needed more space. (The War Department building became the home of the Department of State in the late 1940s.) A few months earlier, at the end of 1940, Stimson had appointed Lt. Col. Brehon B. Somervell as chief of construction for the War Department. The ambitious, driven Somervell had overseen the New York office of the Works Progress Administration, including the construction of LaGuardia Airport in New York. Somervell quickly moved the Army’s camp-building program forward, completing 50 camps and 28 troop reception centers, according to Vogel. That was enough to house the now million-strong Army scattered around the country.

So it was Somervell, now a brigadier general, who first conceived in summer 1941 the now obvious — but unprecedented — solution: one building large enough for the entire department.

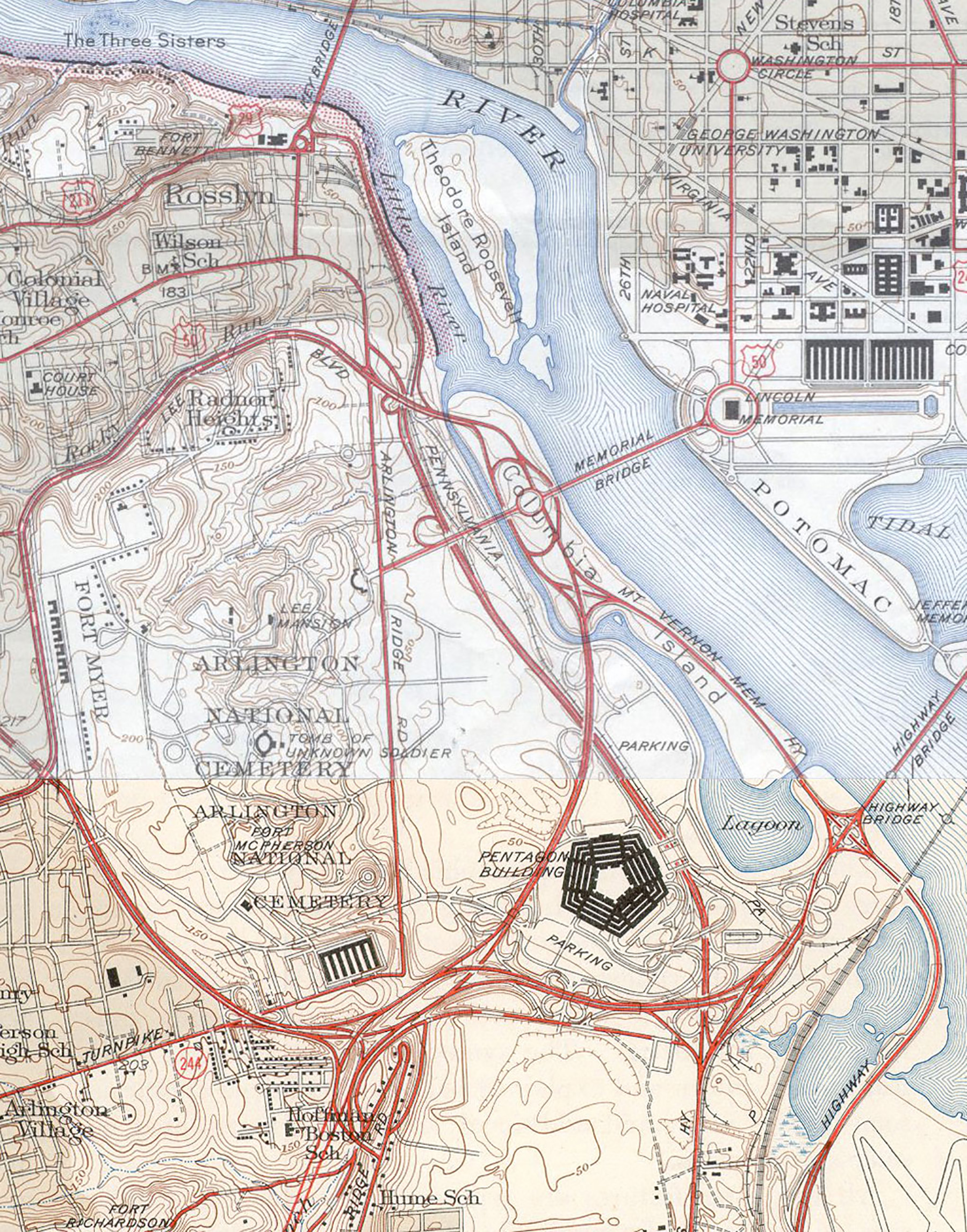

Finding a location was the first challenge. The District of Columbia was too congested. Maryland was too far away. But several sites in Virginia, just over the Potomac River, seemed to offer the War Department plenty of space with easy access to the District.

The main site Somervell wanted was the 400-acre Arlington Experimental Farm, an agricultural research center established on land sandwiched between the river and Arlington National Cemetery. The farm, wrote Vogel, “had once been part of the grand estate of Robert E. Lee that had been confiscated by Union troops in the spring of 1861 for the defense of Washington.”

But there was considerable pushback from the Department of Interior, the budget director, the chair of the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts, and members of Congress, who balked at the rushed nature of the project, its gargantuan size, its proximity to the cemetery, its impact on the visual layout of Washington’s monument-adorned core, and its price tag.

Even FDR had his misgivings about the size and location. At an Aug. 19 press conference, Roosevelt proclaimed his disapproval of the Arlington farm site. He admitted his regret in conceiving while assistant secretary of the Navy the hulking Navy and Munitions Buildings during WWI, which still marred the National Mall (and wouldn’t be demolished until 1970). “It was a crime,” he told reporters, “for which I should be kept out of heaven, for having desecrated the loveliest city in the world — the capital of the United States.” He didn’t want to commit the same “crime” with the Pentagon.

Yet after just a month of debate, Congress approved $35 million (about $580 million today) for a single building that could house 20,000 workers (FDR’s preferred number; Somervell had wanted space for twice as many). In the end, the sprawling 320-acre site would encompass the farm as well as two other parcels: a site for a planned depot for the Army’s Quartermaster Corps and part of the site of the shuttered Washington-Hoover Airport, predecessor to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport.

Construction began on Sept. 11 (the exact day the building would be struck by a plane 60 years later). Somervell pushed for an aggressive timetable — half a million square feet of office ready by March 1, 1942, and the remainder by Sept. 1. His designers had already gotten a taste of the breakneck schedule. A few months earlier, as the initial plan for the Pentagon was being conceived, Somervell had famously given his designers, headed by American Institute of Architects President George Edwin Bergstrom, a single weekend in July in which to sketch out preliminary designs for what was planned to be a 4 million sq ft structure. It would be — and likely will remain — the largest office building in the world.

Bergstrom designed the building’s original form to fit with the irregular geometry of the farm site. Early sketches included two roughly pentagonal ring structures. Over time, the building’s location shifted some, but the pentagon shape remained, and in fact grew more refined, its shape more purely geometric. Each of the exterior’s five walls measured 921.6 ft in length. Four interior rings were added, bisected by radial corridors to speed transit time through the building. The distance from the inner wall of the inner ring to the outer wall of the outer ring, Vogel wrote, was 386 ft. The Pentagon’s eponymous design provided the perfect compromise between a circle — which would shrink walking distances in the massive building — and a rectangle, which would be easier to construct without curved walls.

The exterior was faced with 150,000 cu yd of Indiana limestone. Roosevelt had decreed that no marble be used in one of many efforts to present the building as utilitarian and functional rather than garishly opulent. The exteriors of the inner ring walls were finished in architectural concrete.

Each of the exterior facades, Vogel wrote, was dominated by a central colonnade of 16 columns, bordered by smaller four-column pavilions, which broke up the exterior massing. It was an example of the style known as Stripped Classicism, which Goldberg described as “a synthesis of classical and modern style characteristic of many federal buildings designed between the 1930s and the 1950s” — basically, pared-down classical.

The austerity of the Pentagon’s design helped tame its mammoth size. But there is no doubt that the building was unprecedented in its size. It required 435,000 cu yd of reinforced-concrete (the Empire State Building, then the tallest building in the world, used just 62,000 cu yd). It used 7,754 windows and boasted 17.5 mi of corridors. The overall project would require 30 mi of highways, ramps, and cloverleaf exchanges, along with 21 overpasses, Vogel wrote. The telephone system, meanwhile, required more than 68,000 mi of trunk lines through the building to connect an astounding 27,000 telephones.

Engineers considered wood piles for the foundation but opted against them because of the high water table in the region and an expected delay in the delivery of materials, according to Goldberg. They also rejected steel, which was in demand for military vessels. They opted for cast-in-place reinforced-concrete piles, 41,492 in all, “ranging from 27 ft to 45 ft in length, (with) an aggregate length of more than 200 miles,” Goldberg wrote. They were cast inside steel cores that were then removed, according to Vogel.

Similarly, the building itself relied on a reinforced-concrete frame, which further reduced the amount of steel used — by almost two-thirds. According to Vogel, enough steel was saved to build a battleship.

The scale of the Pentagon was matched only by the breakneck pace of its construction. During construction, as many as 15,000 workers were on-site at a time. The design team included, Vogel wrote, “110 architects, 54 structural engineers, 43 mechanical engineers, 18 electrical engineers, 13 plumbing engineers, various specialists in roads, landscaping, and acoustics, as well as dozens of clerks and messengers.” Meanwhile, another group of more than 100 engineers, architects, and inspectors, located at the construction site, were authorized to make impromptu decisions — the building was truly being designed and built at the same time.

The pace, however, made for an unsafe work site: eight workers died by August 1942. And, typical of big government projects of the era, vulnerable communities often found themselves as roadblocks to be flattened on the path to progress. In this case, construction required demolishing a small and poor Black neighborhood called Queen City. It was a modest collection of homes — many run-down and some lacking toilets. But the community had stores, a barbershop, and two churches, Vogel wrote, “and a feeling of shared history among proud residents.”

Inside the Pentagon, however, there were signs of social progress. Roosevelt had banned segregated bathrooms at the Pentagon — though they had been built — but there were still segregated dining facilities. Vogel’s book lays out the sequence of events that changed that. One day in May 1942, Black ordnance worker Jimmy Harold, a draftsman and engineer, refused to eat in the Blacks-only cafeteria at the Pentagon. Over several days he and other Black ordnance staff sat in the white dining room, over objections and pleas from many. Finally, the confrontation turned violent when a security guard hit Harold over the head with his baton. Judge William Hastie, the Black civilian aide to Secretary of War Stimson, soon learned of the incident and was able to get an investigation authorized. According to Vogel, the inquiry was a bit of a disgrace, but Somervell, once he heard what had happened, ordered the “discontinuance of any enforced segregation of negro employees in the cafeterias in the Pentagon building.”

In July 1942, a fifth floor was added to the Pentagon. When the new building officially opened on Jan. 15, 1943, just 16 months after construction began, it was four times larger than its counterparts in Britain, Germany, and Japan combined, Vogel wrote. At full occupancy later that year, the now 6.6 million sq ft behemoth had a working population of up to 33,000. The final cost of the Pentagon was estimated between $63 million and $75 million (roughly $1 billion to $1.2 billion today).

After the war, the Army demobilized, and personnel at the Pentagon shrank some but not much. Ideas were proposed for making use of unused space — a 15,000-bed hospital, the Veterans Administration (now the Department of Veterans Affairs) headquarters, and a national college for war vets were all put forth. But by this time, the world had changed. The Cold War loomed, the Korean War was just a few years away, and the United States had become the most powerful nation in the world. The Pentagon would soldier on for another 50-plus years.

In 1989, the building was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. According to authors Lester M. Hunkele III, P.E., M.ASCE, Julian Sabbatini, P.E., M.ASCE, and Gary Helminski (“The Pentagon Project,” Civil Engineering, June 2001), by the early 1990s, the Pentagon was out of compliance with contemporary government codes. (“In fact,” they wrote, “the building has failed to comply with the National Electric Code since 1953.”)

So Congress authorized a complete $1.2 billion (more than $2.2 billion today) overhaul of the building in 1993. The Pentagon Renovation Program, known as PENREN, was expected to take 20 years. The building would be renovated in stages, corresponding to the five “wedges” formed by the five exterior sides and extending inward toward the center, and its heating and refrigeration plant would be rebuilt. According to a Department of Defense report to Congress in 2004, “the plan envisioned the complete removal of all mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems down to the base structure due to the widespread presence of hazardous materials and the high probability of systems failure.” The renovation would provide new engineering systems, vertical transportation, information technology systems, lighting, and fire and life safety systems as well as upgrades to enable it to comply with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Better food options, energy conservation, and safer vehicular traffic were also priorities.

On the morning of Sept. 11, 2001, the hijacked American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon, killing 189 people. “From a purely analytical perspective, the plane had hit the building in the best possible place,” wrote Vogel. “The plane smashed into a section of the Pentagon that had just been renovated and was still largely empty.”

According to a Department of Defense fact sheet on the building, “only about 800 out of the 4,500 people who normally would have been working there had moved back into their offices. And the new sprinkler system, extra structural support, and blast-resistant windows helped to keep the building damage to a minimum, likely saving additional lives.”

The reconstruction was handled by British engineering conglomerate AMEC, which had just finished renovation work on what would become the destroyed section of the Pentagon, and Hensel Phelps Construction Co. of Greely, Colo.

Rebuilding the damaged portion of the Pentagon, dubbed Project Phoenix, became one additional part of the ongoing renovation of the building. The goal was to occupy the outermost ring of the impacted section by Sept. 11, 2002 — a goal that was achieved one month early. According to a paper presented by the Project Management Institute, the work required the demolition of 400,000 sq ft of structure and the removal of 56,000 tons of contaminated debris; the installation of 2.5 million lb of limestone; and 3 million person-hours — with only five “single-day lost work incidents” (Pentagon Phoenix Project, by Mike Sullivan and Clark Sheakley. Newtown Square, Pennsylvania: Project Management Institute, 2003).

The PENREN project finally wrapped up in 2011. With its combination of strength and repose, history and innovation, the Pentagon remains one of the defining symbols of the American Age.

T.R. Witcher is a contributing editor to Civil Engineering.

This article first appeared in the September/October 2021 issue of Civil Engineering.